1967

-The Emergency Conference on the Unitarian Universalist Response to the Black Rebellion -

In early October 1967, the UU Commission on Religion and Race held an Emergency Conference on the Unitarian Universalist Response to the Black Rebellion at the Biltmore Hotel in New York City. The conference was called in response to the events of the Hot, Long Summer and to “plan how Unitarian Universalists, locally and denominationally, can help to give a new level of commitment to the Negro and to the cities by setting new local and denominational priorities.”

The conference agenda distributed to attendees started with a quote from Bayard Rustin, who organized the March on Washington. The first conference plenary session included an opening from the UUA President, a session on the purposes of the conference, and session on “The New Black Rebellion”.

More than 134 people participated in the conference and all but two UUA districts were represented. We sent several members of BURR to participate including Louis Gothard, Jules Ramey, and Carrie Thomas. Our church’s associate minister, Roy Ockert, also attended, as did other Angelenos including Kenneth Knight, a newly employed Community Development Worker of the Social Concerns Action Committee, Marion Buell of Throop Memorial Church, and R.E. Bulford of the Studio City Church. There were a total of 34 conference leaders, about a third of which were Black, including the conference chair, Cornelius McDougald. About 20 percent of all conference attendees were Black and mostly represented churches in urban areas, including our congregation.

Soon after the conference began on Friday, October 6, 33 of the Black attendees withdrew from the planned agenda. Mirroring what happened at our own church among those who started BURR, those participants that withdrew from the conference decided to meet separately. That group eventually formed the Black Unitarian Universalist Caucus (BUUC) and installed Louis Gothard as their chairman. During the conference, BUUC created committees on national, denominational, and local affairs, which paralleled three commissions established at the conference.

In a talk given the following year, Ramey explained that BURR planned to initiate the withdrawal from the formal conference agenda prior to the conference. BURR even sent a letter to the UUA advising them of their plan, but received no response.

When BURR decided to challenge the denomination, it certainly was not without awareness of the odds against being successful….When BURR gave advance notice to Boston what we planned [to do] in New York at the U.S. Emergency Conference on the Response to the Black Rebellions, Boston didn’t respond to our letter…BURR members were advise by many and warned not to do this. We would end up making fools of ourselves… “You’ll just end up being 3 silly [n—-s] sitting off by yourselves and being laughed at.”

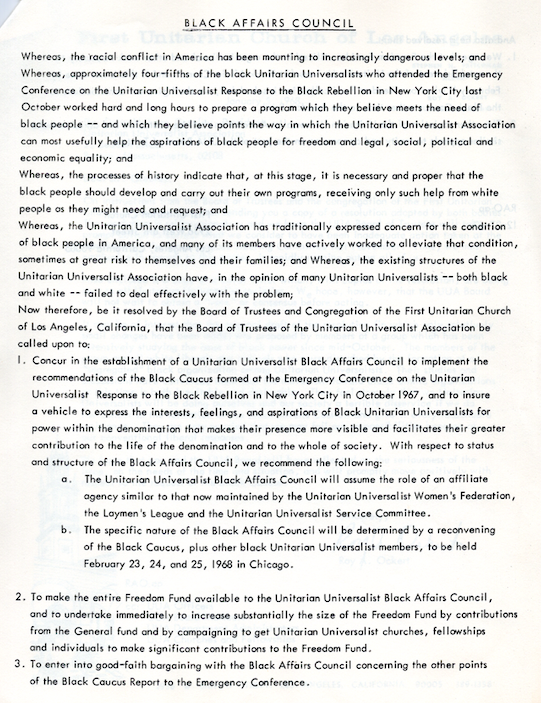

BUUC did not directly participate in the rest of the official commissions in the conference but did attend the plenary sessions. On the final day of the conference, BUUC presented to the final plenary session their joint request and asked that the conference approve it without changes and forward it to the UUA Board of Trustees. One of the proposals from BUUC was the establishment of a Black Affairs Council (BAC) within the UUA to function as an affiliate agency similar to other affiliate groups. They also requested $1 million in funding over four years.

After more than an hour of debate, the request was approved overwhelmingly by the conference attendees.

Ockert shared his observations about the process in a brief report made to the church soon after the conference:

I was impressed by the confident, comfortable, joyous manner with which members of the Black Caucus conducted themselves in plenary sessions. I was told by some of them that for the first time they felt they were really involved in a Unitarian Universalist function. Rather than being scattered islands of blacks in a vast sea of white they were able to get acquainted with other people in similar situations, to discuss mutual problems and to hammer out an agenda relevant to the needs and strivings of black Unitarian Universalists. I think we an all share a vicarious pride in Louis Gothard’s performance as spokesman of the Black Caucus and in the obvious deep involvement of Jules Ramey, Carrie Thomas and Kenneth Knight in proceedings of the Black Caucus.

Ockert lamented that most of the white participants in the conference seemed uncomfortable and excluded from the activities of BUUC, and their misgivings distracted from the work of the conference. Despite those issues, the conference had been a success. Ockert said, “That vote to approve the BUUC request and participation of black Unitarian Universalists for the first time on a meaningful level include me to believe that this was one of the most important events in the history of our denomination.”

Jules Ramey also saw the final vote of the conference as a success, but had mixed feelings about the task ahead:

On January 28, 1968, Ockert delivered a sermon I called “Black Is the Color” about the events surrounding the Emergency Conference. The following month he was asked to be a member of BAC but initially refused because het felt BAC should be all Black. Haywood Henry (now known as Dr. Mtangulizi Sanyika) persuaded Ockert to change his mind, and told Ockert that BUUC had decided to have nine members on BAC, three of which would be white, so Ockert agreed to serve for one year. Among the nine selected, two came from California: Dr. James Clark of UC Berkeley and Roy Ockert of First Church-LA. Althea Alexander, a member of our church and one of the founders of BURR, was elected an alternate.

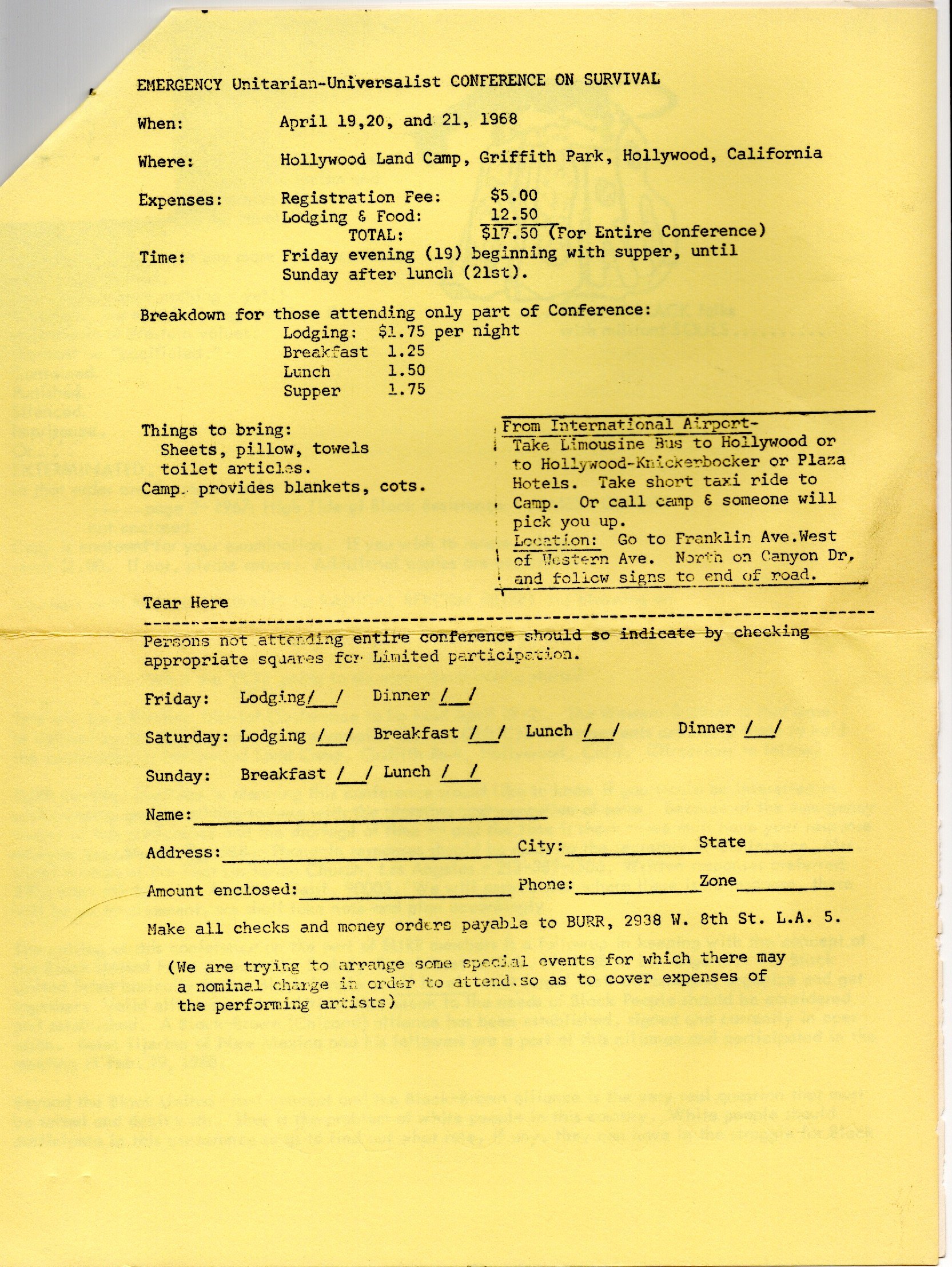

A few months later, in April 1968, BURR helped plan an emergency conference hosted by BUUC for the Western District area, as defined by BUUC. The conference was held at the Hollywood Lamp Camp in Griffith Park, Los Angeles. A flyer about the conference encouraged everyone to participate.

The UUA Board Response

The UUA Board of Trustees considered the BUUC request at their November 1967 meeting and rejected it. UUA President Greely gave the following comments on the specific point of establishing a Black Affairs Council: “We have long advocated an integrated society. It is the temper of the board that we would not today honor or give funds to any group which organized on purely racial lines.”

The UUA Board, for its part, recognized the absence of substantial participation of non-whites within the UUA “deprives us of the enlightenment of the viewpoint of persons to whom our society has not yet accorded full status of citizens.” Its alternative plan involved directing the reorganization of the Commission on Religion and Race to include substantial participation of non-whites and invite participation of BUUC to assist churches and fellowships.

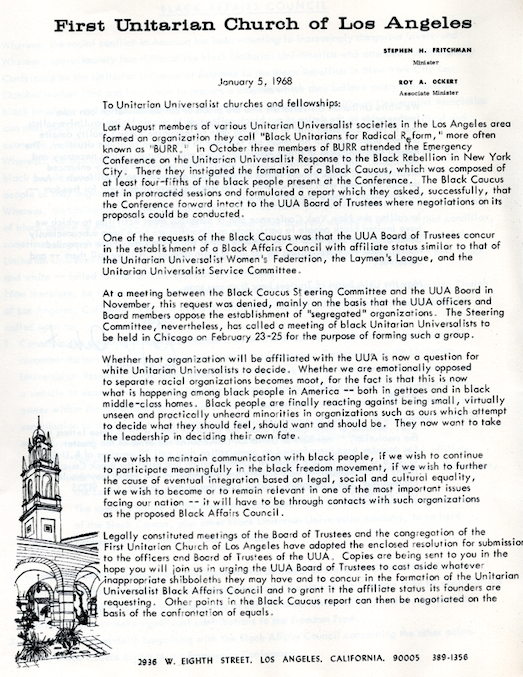

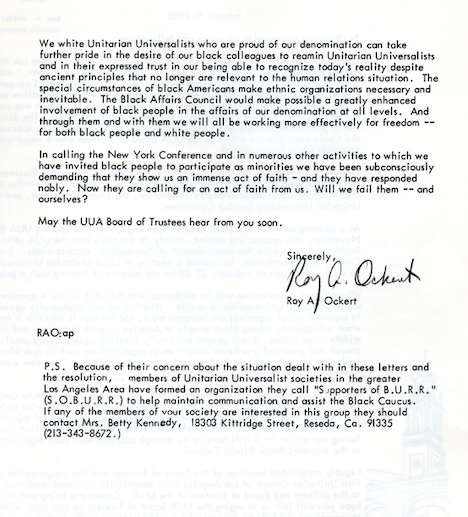

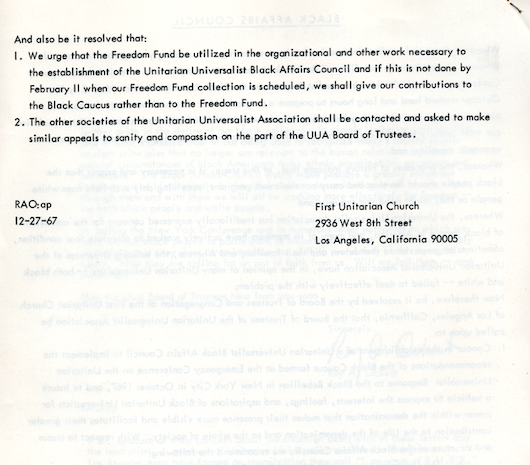

Our church responded quickly. We passed a resolution which requested that UUA board reconsider its decision and expressed our church’s concurrence with the recommendations of the BUUC and explained that those recommendations ensure “a vehicle to express the interests, feelings, and aspirations of the black Unitarian Universalists for power within the denomination that makes their presence more visible and facilitates their greater contribution to the life of the denomination and to the whole of society” . That resolution was forwarded to the UUA Board of Trustees.